Source: HH Brent Blog

Bottom Line: A new upstream gas investment in India could create more supply competition in a key end market for U.S. LNG. Moreover, India’s downstream gas market is already demonstrating some difficulty in absorbing the initial cargoes from its long-term U.S. LNG contracts.

Market Context

Despite the size of its economy, India is only the world’s 13th largest gas market (~5.7 Bcf/d in 2018)

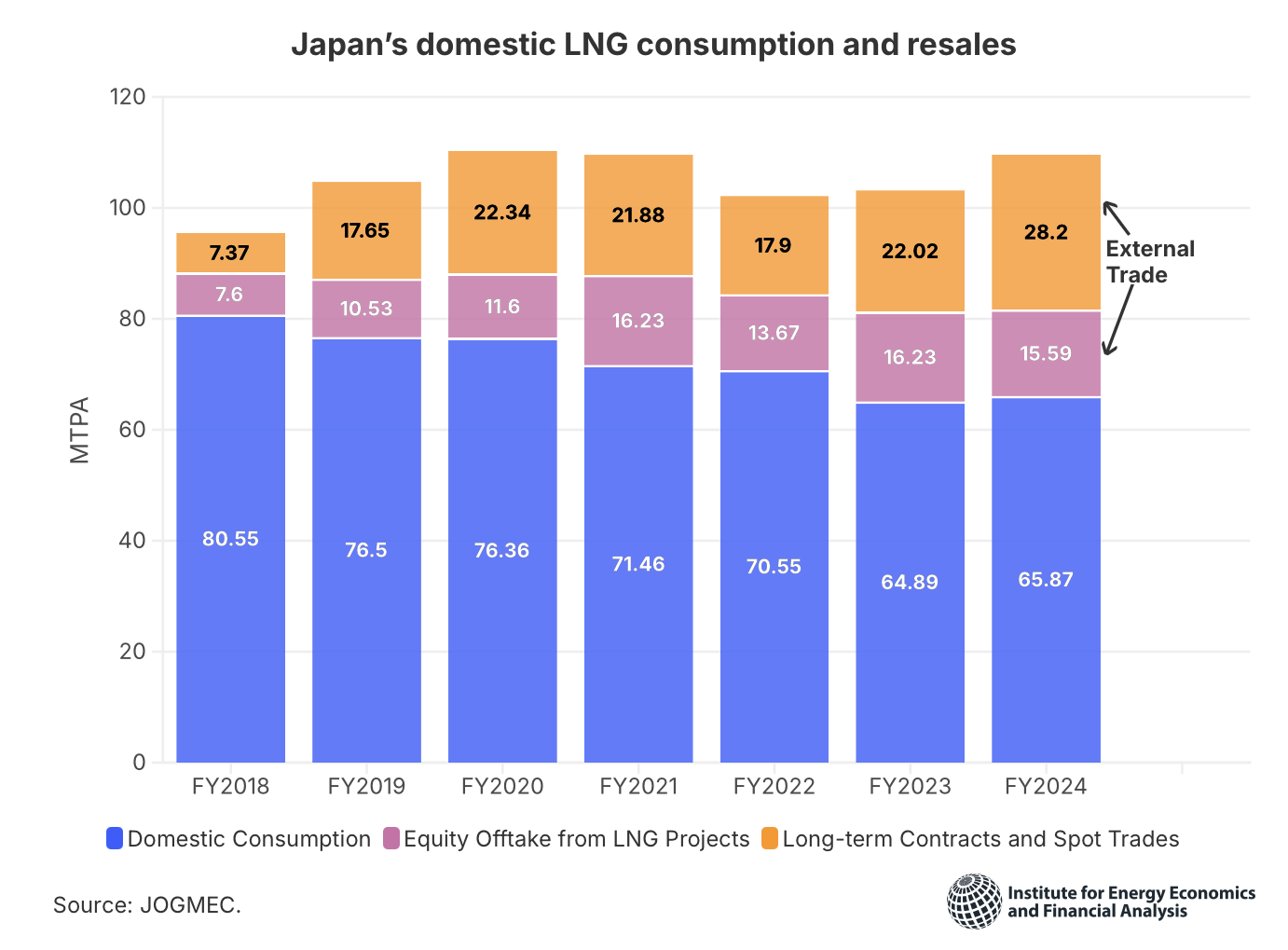

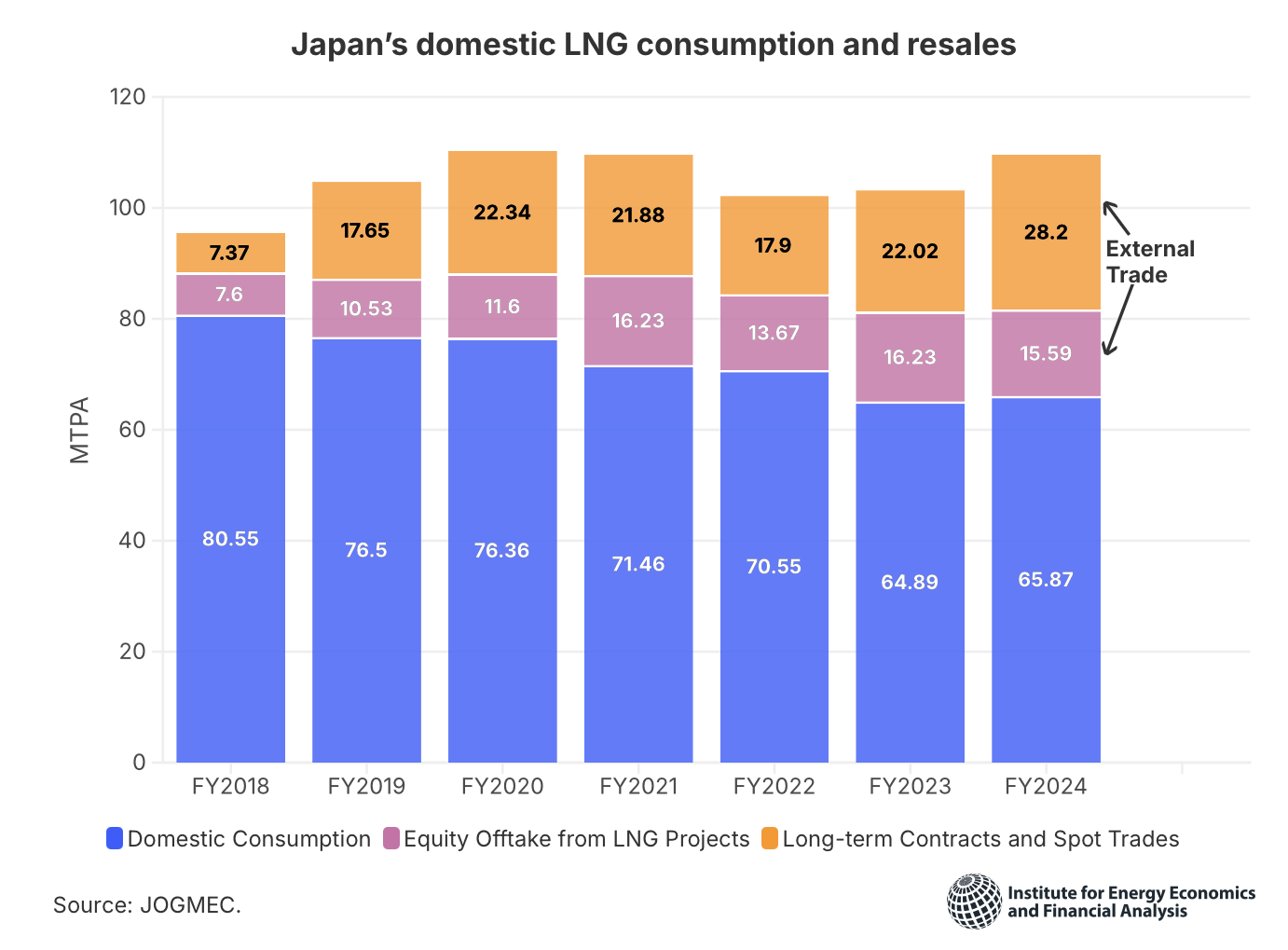

One of India’s largest gas utilities, GAIL, is a key contractor of U.S. LNG export capacity at Sabine Pass and Cove Point totaling ~0.7 Bcf/d. As discussed later, it appears that not all of these volumes will, at least initially, reach the Indian market.

Gas forecasters at leading global energy companies have placed India in the “too big to fail” category with high expectations for the market’s demand growth during the next decade. GAIL and other Indian companies have many long-term LNG supply contracts coming online sourced from multiple suppliers. The Modi government has also set ambitious goals for gas penetration growth, underpinning the high expectations of the forecasting community.

But as discussed at the end of this post, it is not yet clear whether the demand forecasts for the Indian gas market can be met at any cost. To bring these volumes of gas into India’s downstream market – whether via LNG or domestic production – a considerably higher gas price is required compared to what most existing Indian consumers are accustomed to paying.

More Domestic Gas Production on the Way for India

BP and Reliance are moving forward with a new investment in offshore India dry gas production. The new upstream development is expected to plateau at 1 Bcf/d in the early to mid 2020s.

Impact on U.S. LNG Exports

Declines in domestic gas production in gas markets around the world have have been a key driver of contracting activity for the U.S. LNG trains, which have successfully reached construction phase. The Indian market is front and center in the ranks of supply constrained gas markets. At a macro level, commercial success in improving domestic gas production in India or elsewhere is likely a long-term, bearish signal for the growth of U.S. LNG exports.

Success is Not Certain – Checkered History of India’s Upstream Gas Sector

This is not the first time Reliance has invested in India’s upstream gas market. The first investment in the KG-D6 area was the source of great controversy.

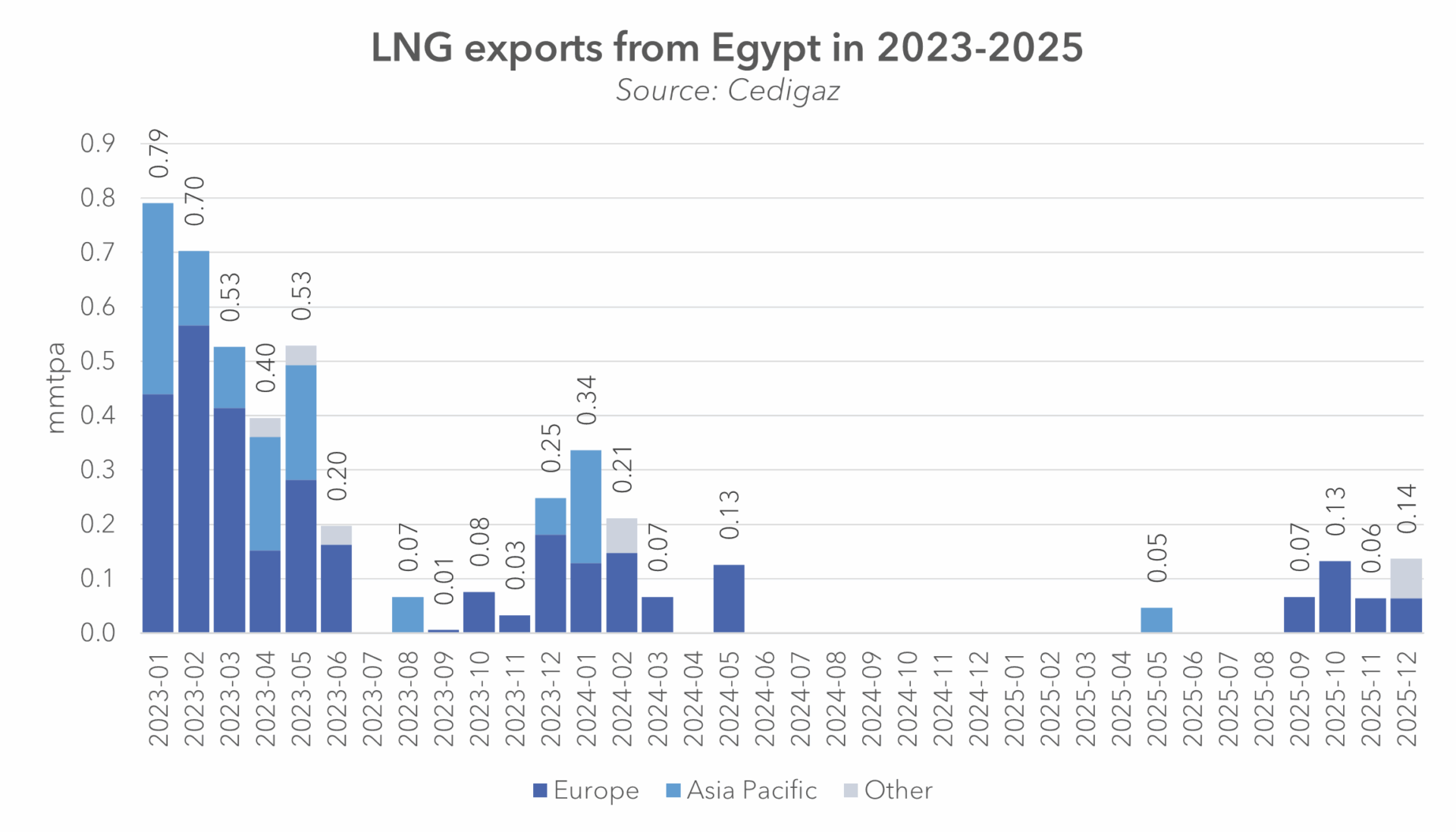

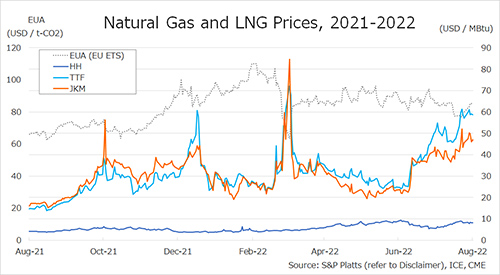

After briefly supercharging India’s gas production towards the end of the 2000s, the field experienced dramatic declines reportedly due to poor upstream fiscal incentives in the original contract. (Click here to see an EIA graph of Indian production.) Downstream investments, particularly for new power plants in the power sector, were left in the lurch. Relatively expensive Qatari LNG imports came to the rescue to stabilize gas supply.

BP and Reliance were willing to move forward with their offshore development plans because they secured the price of gas that they needed to meet their desired level of financial returns. This was the source of great negotiation with the Indian government, which still maintains a very high degree of regulation over natural gas prices.

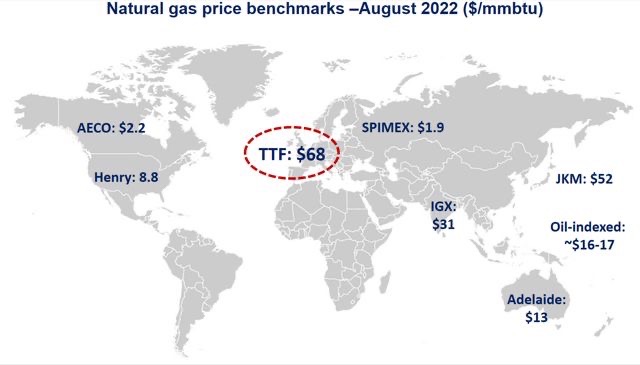

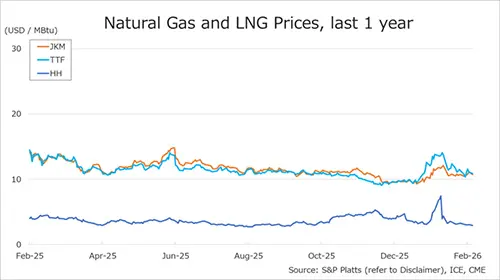

India’s regulated gas price for consumers: $3.06/MMBtu in 2018

India’s regulated gas price for domestic deepwater production (including BP and Reliance’s planned KG-D6 investment): $6.78/MMBtu in 2018

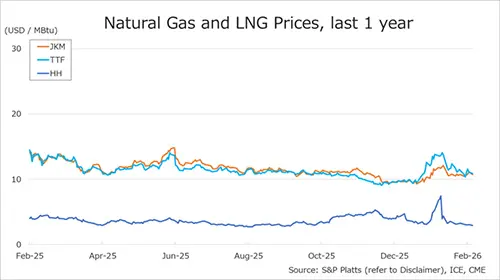

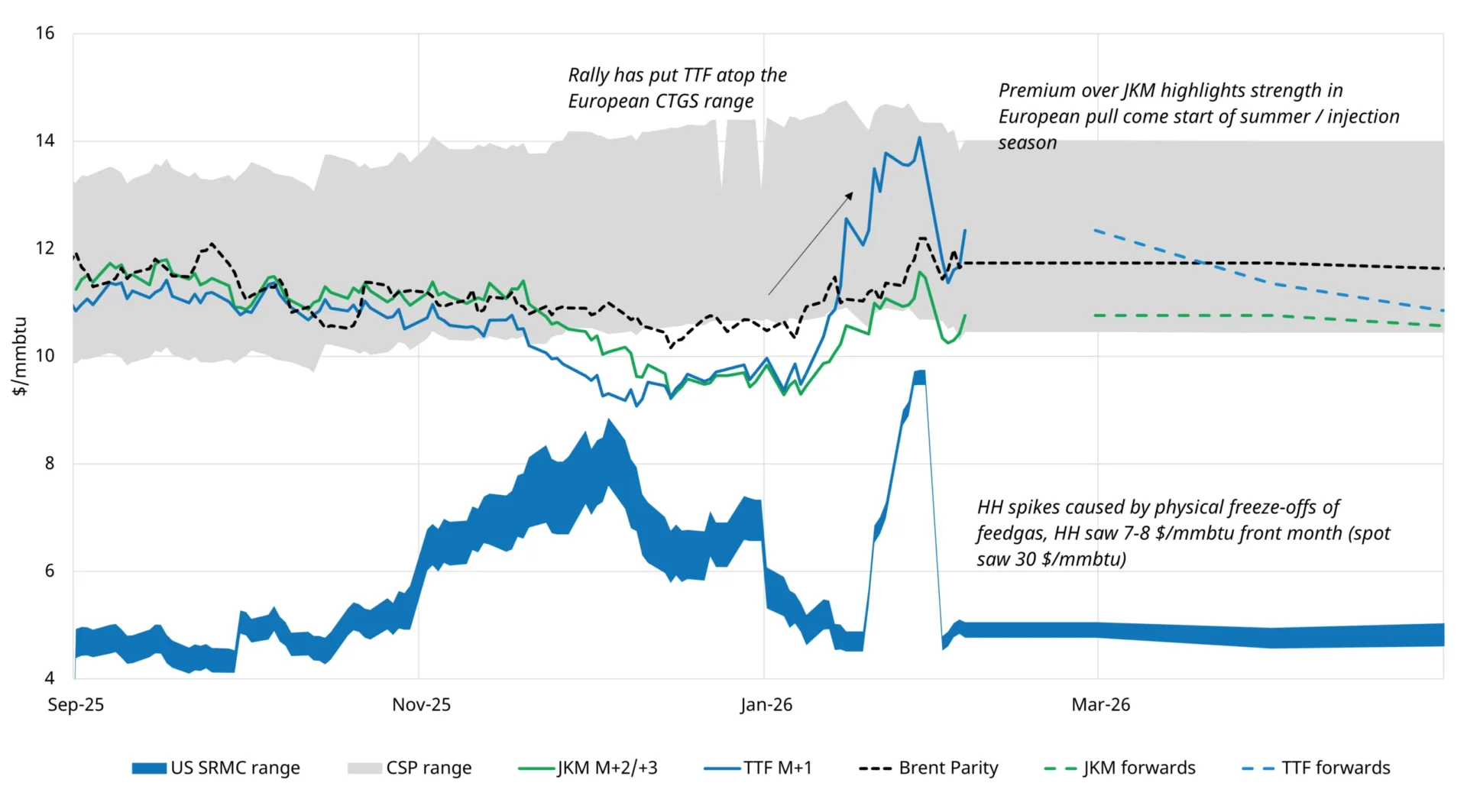

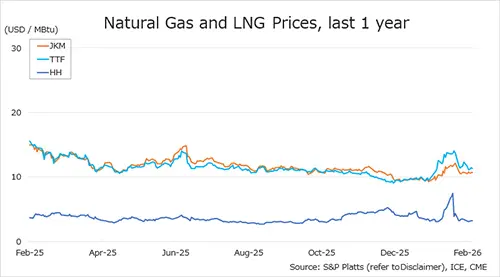

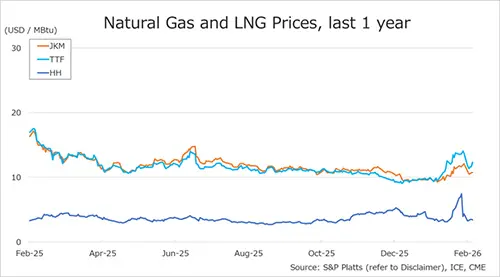

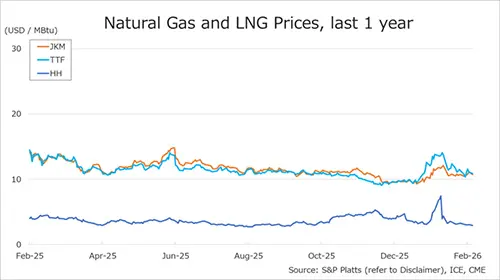

Estimated Range of Long-Term LNG Contract Prices for Indian Market: $7-$10/MMBtu*

*Assumes $3/MMBtu Henry Hub and $65/Bbl Brent

Analysis – Indian Gas Demand Growth at What Price?

The gas price set to promote more difficult domestic offshore production is also competitive with the price of LNG imports. For the moment, prices for either forms of supply are significantly higher than the regulated downstream price. Unless regulators succeed in pushing the downstream gas price higher over time, some entity will need to subsidize the difference on their balance sheet. The financial burden will only increase as higher cost imports and deepwater production make up a bigger share of India’s supply mix rather than its cheaper legacy gas production.

So which segments of the Indian economy are able to justify consuming gas at a higher price? Furthermore, how much more cost will need to be added into gas prices to account for the financing of additional infrastructure necessary to bring gas to more consumers?

Higher Prices Present a Tough Slog for Gas Marketing?

There are many indicators that suggest GAIL is so far having some difficulty placing its long-term contracted LNG volumes with Indian downstream buyers. Ideally, they would be able sign downstream supply agreements on a long-term basis to match the term of their LNG contracts.

Read here about the reworking of GAIL’s Gazprom contract, here about its deal to offload U.S. volumes to Shell and here about its recent tender to part with many of its first Cove Point cargoes that still remain following the Shell deal. All of these stories suggest GAIL is stalling the pace of its import ramp up as it scrambles to find buyers in India’s downstream gas market.

It will likely take time for GAIL to convince Indian energy consumers of the merits of consuming natural gas at a $7-$10/MMBtu. Although these prices are equivalent to about $50/Bbl crude, energy consumers switching from another fuel will also need to account for one-time costs involved in switch fuels or make other process changes.

As always, there might also be more subjective or political factors at play that could explain GAIL’s difficulties. These include ongoing regulatory incentives that encourage consumers to continue to rely on their existing fuel, or legacy business relationships for fuel supply that might discourage a consumer from working with GAIL.